Human relationships: the Achilles’ heel of a contactless world

A loss of relationship quality

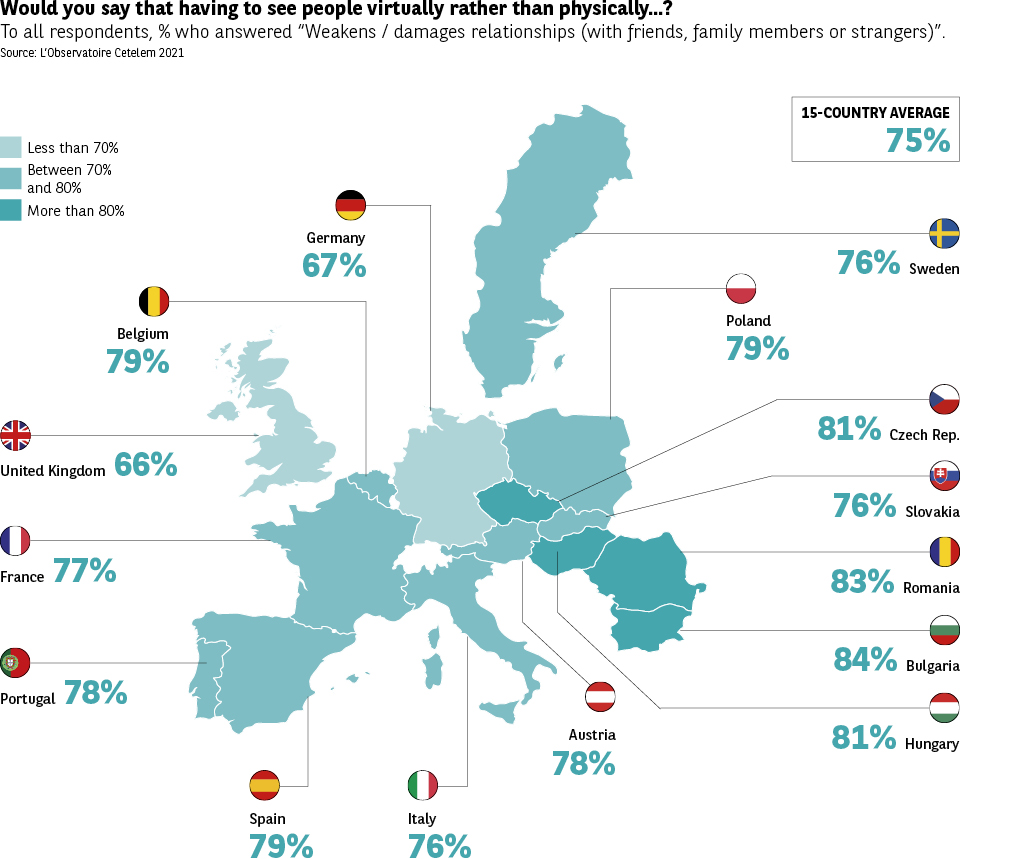

Looking at their testimonies, it is clear that Europeans appreciate the practical side of contactless living, particularly for day-to-day tasks. However, in a more latent way, they express serious reservations regarding the relationship quality it engenders. And when the same Europeans are questioned in greater detail to find out whether life without physical contact weakens or even damages human relationships, the answer is clear and unequivocal. Three-quarters state this to be the case (Fig. 30). Once again, most of the countries in the Northern group, which tend to have greater experience of the virtual world, are more divided on the topic, particularly the British and Germans (66% and 67%). And, as is often the case, we must look to the Central European countries to find opposing views. The Bulgarians, Romanians, Czechs and Hungarians are the most likely to decry the distance that has grown between people (84%, 83%, 81% and 81%). The Latin countries fall between the two, posting scores closer to the European average.

« There are no longer any limits to intimacy. »

Alone together, the horizon of possibilities for contactless relationships

American psychologist Sherry Turkle is a professor of social sciences and technology at MIT. In 2011, she published Alone Together, an essay that made a real splash and helped pave the way for further thinking on contactless living. According to Sherry Turkle, the latter marks a shift from communication to connection. New technologies appeal to human beings because they capitalise on their vulnerability. They avoid us having to make direct contact and give us control over our lives by allowing us to erase and rework what we don’t like and to add what makes us feel good. The feeling that no one is listening to us is counterbalanced by the fact that machines do. I am not alone in being alone. Existence could therefore be summed up by a slightly modified philosophical statement: I share, therefore I am.

Less direct contact

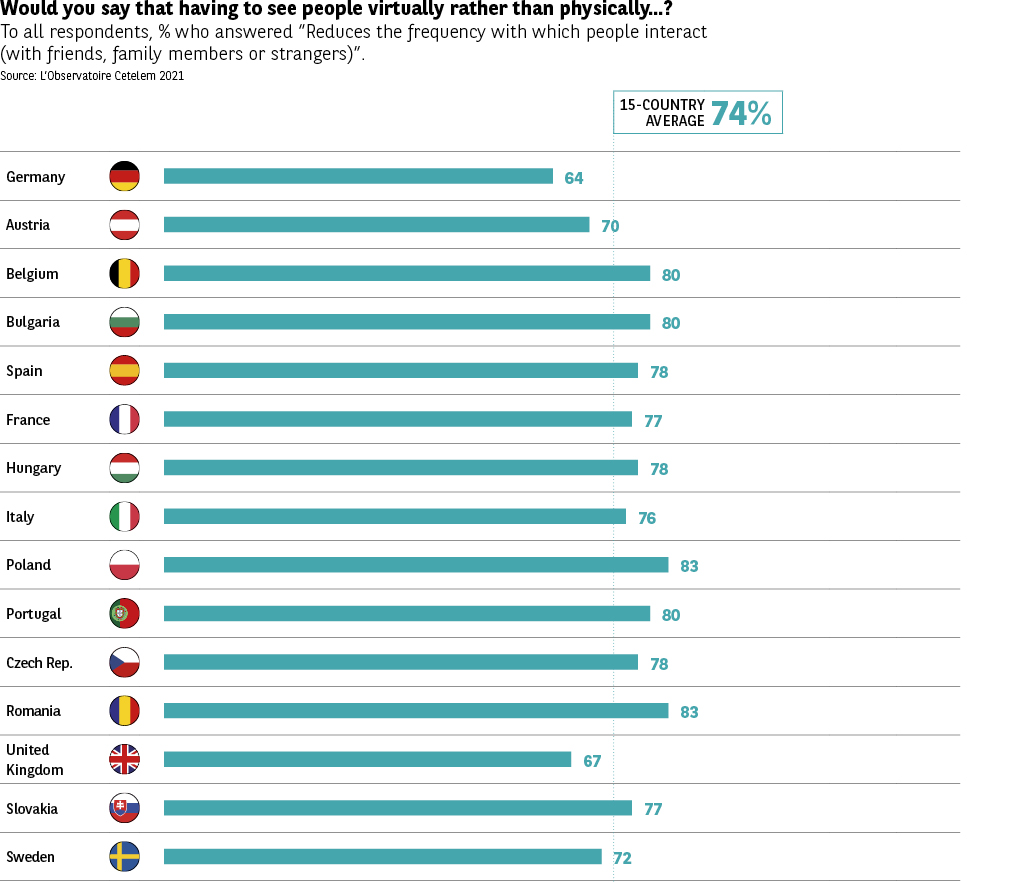

The result could be described as a negative spiral. Not only is the quality of relationships being affected, their quantity is too. Once again, three‑quarters of Europeans believe that contactless living leads to a reduction in the frequency of interaction within relationships (Fig. 31). The differences between the three geographical groups are again very pronounced, with Germany and the United Kingdom in the North appearing less concerned (64% and 67%) and Poland and Romania in Central Europe struggling more with the idea (83%).

Virtual by choice

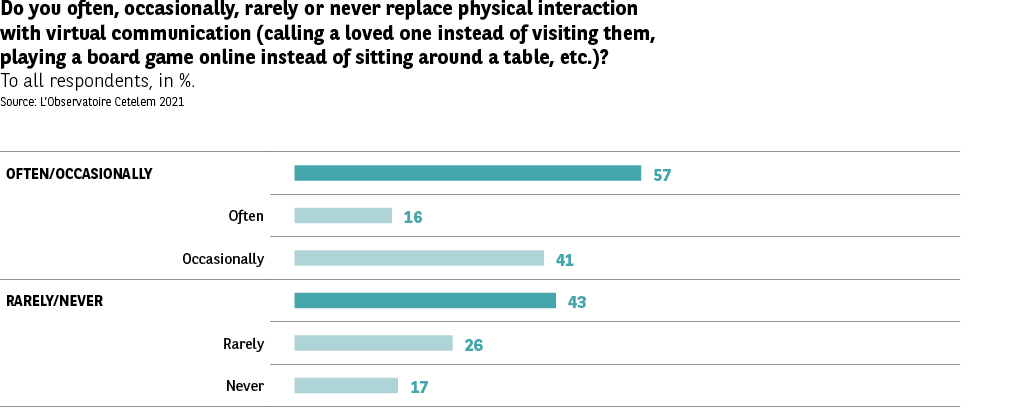

The preeminence of the virtual over the real is not something that has happened against the will of Europeans. In fact, it is a deliberate choice for just over half of them. 57% say they tend to replace physical meetings with remote interaction, whether it be to chat or play games online (Fig. 32). On this topic, all countries except Austria and Hungary post scores above 50%. But this time, no geographical groups emerge from the answers given. Thus, the Swedes, Poles and Spanish, whose countries fall into three different groups, are the most likely to opt for virtual solutions (64%).

« Social ties are deteriorating despite social media. We’re losing our humanity. »

Extimacy, self-promotion through contactless means

Following on from the work of Lacan, psychiatrist Serge Tisserand developed the concept of extimacy, which is facilitated by social media. Extimacy is defined as the desire to fill the void of one’s own existence, to have it validated by others, to fight boredom and to reevaluate oneself. This means publicly sharing certain facets of one’s private life and revealing certain aspects of oneself, be they physical or psychological. Ultimately, sharing this information and receiving likes serves to boost one’s self-esteem.

Social distancing is a source of dissatisfaction

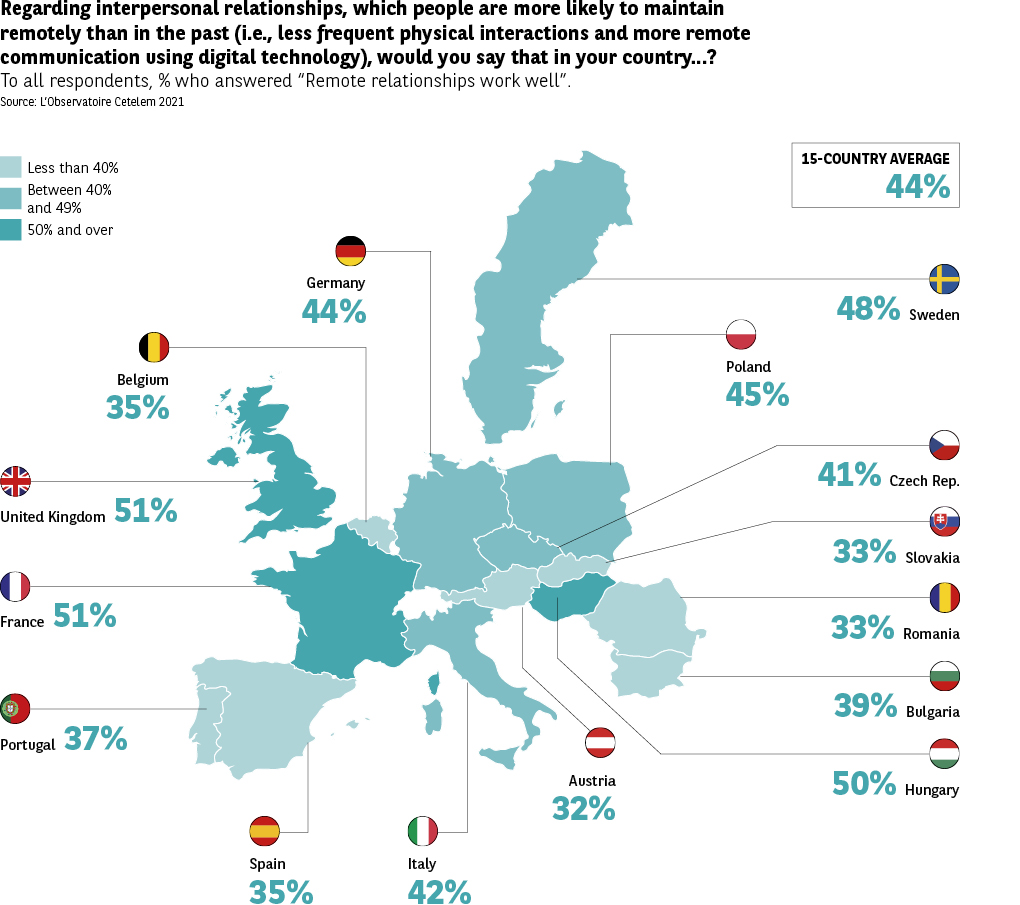

The feeling that a life of contactless relationships is no panacea is widespread among Europeans. Only 44% believe that this type of human relationship works well. The French and British are the most likely to hold this view (51%) (Fig. 33). Generally speaking, contactless interaction is least unpopular in the Northern countries, such as Sweden, while it is perceived more negatively in the South, particularly in Spain and Portugal (35% and 37%). Romania, another country with Latin cultural roots, is even more critical (33%).