AUTOMOTIVE AND DIGITAL WORLDS COLLIDE

What do we mean when we talk about connected cars and autonomous vehicles?

A connected vehicle is capable of communicating and exchanging information with the outside world in real time.

The connected car is already a reality.

Using its sensors and connectivity systems, the vehicle is able to communicate a plethora of data about its position and speed, the condition of its parts, the pressure in its tyres and even about the driver and their behaviour. In turn, the car can receive a variety of information about traffic conditions, the availability of parking spaces and the presence of actual or potential hazards, to give just a few examples. Connected vehicles also allow their occupants to interact with the rest of the world, for communication or entertainment purposes (multimedia).

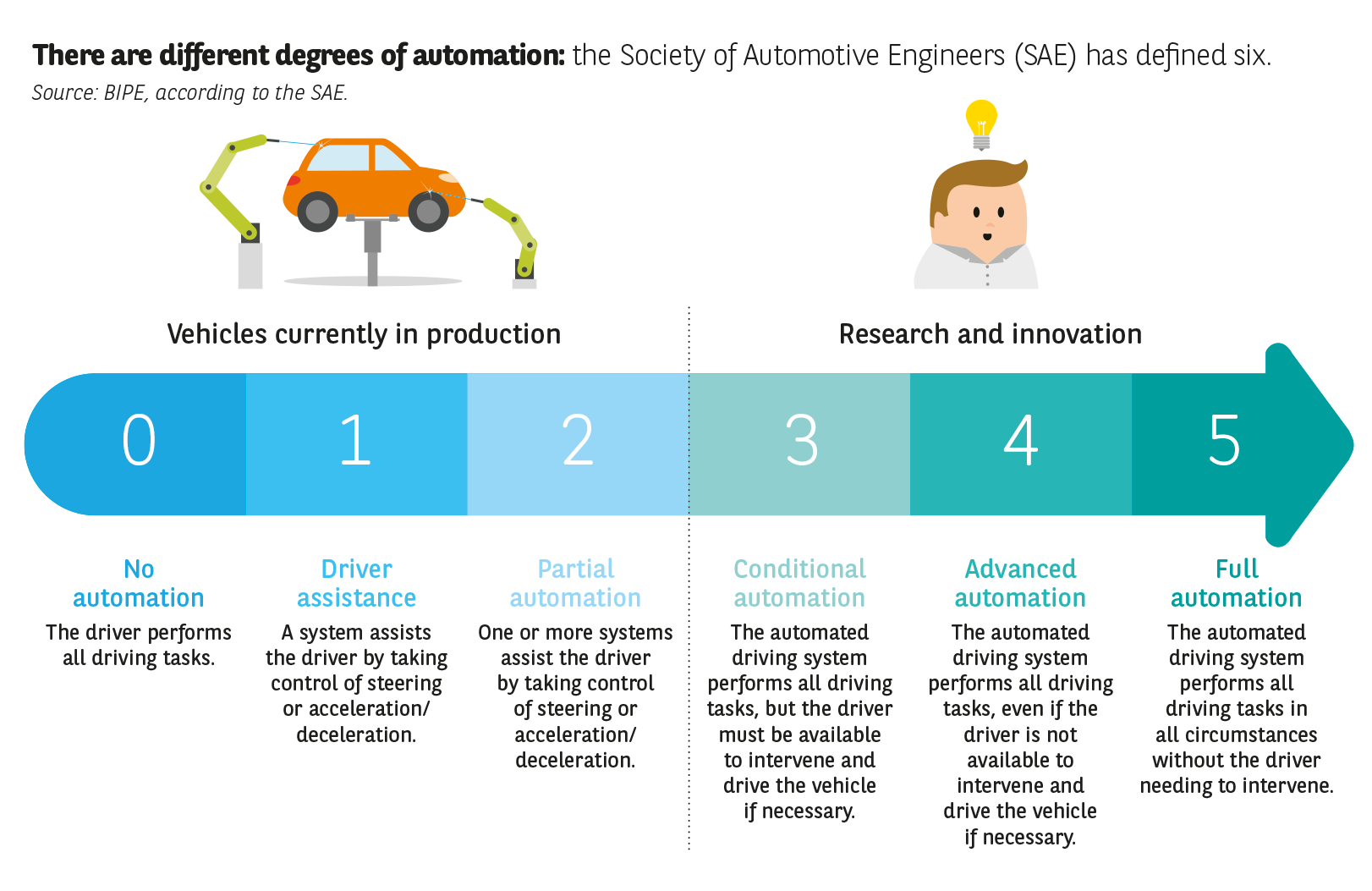

The most advanced examples of connected cars will become increasingly intelligent, with the ability to process data so as to “make decisions” on the driver’s behalf. This decision making can go as far as taking over driving duties entirely, making the car autonomous (Fig. 1). The vehicle’s intelligence, i.e., its ability to assess its environment and act accordingly, relies upon detection devices (GPS and sensors: lasers, cameras, radars, etc.), representation systems (maps), short-range connectivity technologies (allowing vehicles to communicate with each other and with the infrastructure) and decision-making systems (algorithms).

Fig. 1 There are different degrees of automation: the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has defined six.

Source: BIPE, according to the SAE.

From prototype to reality: the concept of a fully autonomous vehicle comes to life.

The idea of making cars autonomous is almost as old as the car itself.

Already in 1939, when General Motors presented the “Futurama” exhibition as part of the New York World’s Fair, designer Norman Bel Geddes had imagined motorways on which remote-controlled cars would travel at high speed in complete safety. As the announcer stated: “Isn’t it incredible? What you have before you is the world as it could be in 1960! ” A few years later, in 1958, the same group road tested the Firebird III, which was equipped with an automatic pilot and capable of following a cable laid beneath the road. In 1984, German professor Ernst Dickmanns and his teams from the University of Munich sent a Mercedes-Benz van down an empty motorway at 96 km/h, without any human intervention. In France in 1996, the INRIA presented the Cycab prototype, a vehicle that illustrated the potential of robotics for urban travel.

Research on autonomous vehicles has been performed in numerous countries for many years.

The concept truly began to gain ground in the 2000s: significant progress was made in the research sphere, particularly in the United States when the DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) decided to organise two races, in 2004-2005 and in 2007, with a sizeable financial reward for anyone who could create a vehicle able to travel a given distance without human intervention. The contest prompted the birth of the first prototypes of smart, driverless cars. The 2005 Grand Challenge prize was won by an electronics research laboratory based at the University of Stanford, one of whose members would go on to become the research director of the Google project! His prototype, the Volkswagen Touareg Stanley, travelled 212 km in the desert completely autonomously.

Today, the famous Google Car has covered a distance of almost 3 million kilometres, including more than 1.5 million fully autonomously. The firm has stated that it will be ready to launch the first vehicles on the market in 2020. Tesla and Mercedes-Benz, to name but two, have set themselves the same objective. The race to develop the first fully autonomous vehicle is on!

Preventing regulations from becoming an obstacle

“The problem is not technology. We have to work on regulations and responsibility,” declared Patrick Mercier-Handisyde, Director General of Research and Innovation at the European Commission.

The state of progress of the regulatory framework for autonomous vehicles is not the same in Europe and the rest of the world.

The United States, a pioneer in this field, updated its legislation a number of years ago. Local regulations already allow trials to be performed in California, Florida, Nevada and Michigan. Audi, Google and Mercedes-Benz were the first companies to obtain a licence to test driverless vehicles. In 2012, California passed legislation setting forth safety and performance rules for the testing of autonomous vehicles on main roads and motorways. These rules require the presence of a steering wheel, pedals and a driver who is able to take manual control of the vehicle. At federal level, American road safety bodies are still examining the topic.

In Japan, a national programme has been launched for the development of autonomous vehicles that are 100 % Japanese. At the end of 2013, Nissan received approval to operate its autonomous Leaf. Autonomous driving tests will soon be launched on public roads, notably a “robot taxi” service in Kanagawa, while the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo will be the chance to give demonstrations of autonomous vehicles.

Regulations are also being updated in China, to provide a framework for testing and launching driverless vehicles on the market.

Elsewhere, particularly in Europe, but also in Brazil, Mexico and South Africa, the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, which came into force in 1977 and was ratified by 72 countries (not including the United States, China and Japan), does not allow autonomous vehicles to operate on public roads, as it stipulates that the driver must have their hands on the steering wheel at all times, must be in full control of their vehicle and is entirely responsible for the latter. However, a think tank is now working on an amendment to this convention, which could be adopted by 2017.

In Germany, a draft bill is being prepared that will allow autonomous cars to be tested on a stretch of motorway between Berlin and Munich. In the United Kingdom, legislation is expected to be brought in by 2017 to cover the testing of autonomous vehicles. In France, following the launch in 2013 of a plan to regain ground in the field of autonomous vehicles, the 2015 law on the energy transition allows the government to adjust legislation “so as to permit the operation on public roads of vehicles to which driving is fully or partially delegated”. Tests began at the end of 2015 and large-scale trials are due to commence in 2016 involving 3,000 smart vehicles running on half a dozen connected roads of different types (2,000 km of dual carriageways, motorways and main roads). If the trials are conclusive, the widespread introduction of these vehicles will be considered the following year.